Todays adventure came to me as a surprise, because I was told it was a pristine abandoned hospital, and not an utterly trashed cancer research laboratory. Nevertheless, an adventure's an adventure and I'll take it where I can get it.

It was a minor challenge to get in, a feat achieved by getting onto the roof, standing on something precarious and then hurling myself through a teeny hole. And lets be honest, that's way more exciting than walking in through a wide open front door. I know that will dissuade the casual pin-swapper urbexer, but not the vandals!

It turns out this place actually has a story too! But it involved wading through pages and pages of terminology completely alien to me, so I'm probably going to butcher a few scientific terms, get a few things wrong, and make the entire scientific community cringe or cry. That's your disclaimer right there. If you want scientific accuracy and intelligence above that of a lemon, then you've certainly come to the wrong place because I haven't a clue what the fuck I'm talking about.

But fuck it. I'll also be insulting everyone with a camera today, because these pictures are garbage. They're the result of exploring at night time, armed only with a camera and a torch, and also distracted by the fact that I wasn't alone here- others were present and they were smashing the place to pieces like the good, civilised humans that they aren't.

Let's dive in, starting at the front desk!

The lab owes its existence to a number of people, predominantly a chap we'll call Hal. Hal was born in 1905 and came from humble beginnings. His father was a post office telegraphist who regularly bounced mathematical problems off him during their long Sunday walks. His aunt inspired within him a love of furniture making when she showed him how to make a bookshelf out of old crates. He was apparently bored by languages and sang like a canary when the schools abolished mandatory Latin, but later discovered a love for literature when he attended Cambridge University and read books to a blind student who would become his wife. But his real interest was nuclear physics, and his ultimate goal was to use science to benefit mankind. To this end he even declined an invite to return to Cambridge during the war to work on neutron research for the war effort, because he refused to apply his mind to military research.

Instead, when he noticed that a hospital was looking for a physicist to study radium and x-ray radiation on living tissue to treat cancer, he jumped on it. And he was a bit of a genius too! In 1936 he developed the cavity ionisation method of measuring radiation doses, which I *think* means measuring an electrical current created by radiation interacting with gas inside a chamber. Hal also built his very own neutron generator in 1937, which I think is basically a particle accelerator that in the field of cancer treatment is used to beam radiation at targeted cells, and also (I think) measuring the effects of that radiation. That makes sense. Why would you hit biological matter with radiation if you have no means of measuring the result, right?

It's quite impressive to have built one in 1937. It's 2022 now and I still can't build one. But alas, Hal clashed with the units director quite a lot, with one significant bust up being because he wasn't consulted before establishing safe radiation doseages before starting radiotherapy. It's a fairly understandable concern. Nevertheless, the squabble was severe to the point that he was forced to resign.

Three

other scientists also decided to resign as a form of protest, taking Hals side in

the whole silly debacle. Among them was a chap called Oliver. Oliver was a radiobiologist but also stinking rich, being the third baronet of a peerage created in

1909, thriving in the cotton industry. He was a massive fan of Hal. In the 1950s he himself contributed to cancer research. While it was known for some time that a tumour that had grown to the point of being starved of oxygen (Referred to as a Hypoxic Tumour) was more resistant to radiation treatment, Oliver was busy demonstrating that applying high pressure oxygen to these hypoxic tumours could double their sensitivity and make them easier to destroy. He wasn't unique. By the 1950s numerous other medical

experts and scientists were coming to the same conclusion, but in Olivers case, Hal was ther only person who took him seriously. Is it any wonder Oliver stuck by him when he needed support?

Oliver

and Hal decided that despite their defeat in the world of radiotherapy,

they should publish their work so far anyway, if anything to save Hal's reputation. This publication detailed all of their research into hypoxic

tumours, and essentally saved their careers

When the publication went out in 1953, the data was still incomoplete, likely due to the circumstances that Hal departed his workplace, but it was enough to prompt clinical trials that combined radiotherapy with oxygen therapy. Forty years later this paper was

still being quoted aproximately 20 times a year in world literature.

Oliver was famously modest but even he admitted "if citation is a fair measure of

success then we've done rather well." Oliver then negotiated with the medical research council, donated the funding himself, and then this laboratory was set up, opening its doors in 1957. Hal, despite

being a lover of tea, totally forgot to include a tea kitchen in his

original designs, a mistep that his friends, colleagues, and himself,

had a good chuckle about for years to come.

Now that same lab is sprawled out in front of me, trashed and ruined, and

perhaps the last thing that should ever be left abandoned.

Theres a diary behind the front desk which seems to be detailing the whereabouts of certain staff members. On the 13th March 2008, Loretta and John were on holiday, and Giselle was out, but not at Oxford. The Boris Boris bit confused me, but then I noticed that on the following page it says that Boris is in Paris. Well that's alright. Someone's just gone back over to make it look like it says Boris Boris.

The office also has this little shelving unitt with different bits for different staff members.

I have no idea what this gizmo is.

The halls of the laboratory are obstacle courses of rubble. The local thugs have not been kind to this place.

Now here's something genuinely fascinatng and new to me. Arachnophobes might want to close their eyes and scroll for about three seconds.

The labs arachnid population seem to have succumbed to a fungal infection that has taken over their bodies. This particular fungus is Engyodontium Aranearum, and it seems that the Cellar Spider, Pholcus Phalangioides, is particularly vulnerable to the fungus.

This is actually because of a completely unfortunate design flaw on the Cellar Spiders body. You see, their legs have extra joints compared to other spiders, and for them to function properly, they have a thinner exo-skeleton that the fungus exploits.

It's an unfortunate fate for them, because the fungus doesn't just kill them straight away. They have to go about their day and move around so that the fungus can launch its spores at other victims, while the fluffy white stuff engulfs them and eventually eats their brain when its finally done.

Poor little buggers. The good news is, this fungus doesn't effect humans. But imagine if it did! Imagine the zombie apocalypse with fluffy marshmallow people!

Back to the labs!

Despite the trashed hallways, the labs seem to be oddly clean.

Of the activities that took place here, early research involved the development of pulse radiolysis, which is basically delivering the radiation to the target cels via pulses instead of a steady set beam. It was thanks to pulse radiolysis that the hydrated electron was discovered in this building back in 1962, and while I'm not 100% certain what this means for cancer patients, I do know that their discovery set in motion an entire new direction of research that is still active to this day.

The lab also continued the oxygenation of the hypoxic cancer cells.

Here's a copy of Microsoft Word from two decades ago, still in its package. It's the version that has that adorable paperclip!

Amongst the vandalism, the phone is still on the hook. That's weird and oddly creepy.

With Hal running the place, Oliver continued to work here, carrying out tests on mice, and measuring re-growth delay. His research contributed to stem cell identification, cancer oxygenation, transplanting antigens into tissue to fight cancer, and also eliminating any negative effects of it, and also pushing for the use of multiple treatments each day to combat fast growing tumours. His experiments with mice seem to get a lot of credit, mainly with him stressing the need to use inbred mice only instead of mice from different genetic lineages. I think this has something to do with measuring radiation doses and getting consistent results by using animals with similar natural resistance.

When Hal died in 1965 following a stroke, Oliver took over the lab. He was also forced to resign himself in 1969, due to failing health. But he still continued to support and fund research. He started his career struggling to be taken seriously, and in retirement he was such a renowned scientist worldwide that he was even invited over the Soviet Union in the 1970s, during the cold war, to help investigate the effect of soviet nuclear testing on the population of Kazakhstan. That's pretty cool.

Following Olivers retirement, a chap called Jack took over the laboratory, running it from 1969 until 1988. He obtained a physics first class honours degree when he was just nineteen, but had mainly just worked on spitfires during the war. He dropped out of physics during the development of Hydrogen bombs, not wanting to be associated with all that destructive nonsense. Instead he joined the theatre for a bit, before coming here to research cancer treatment.

His leadership really helped increase the reputation of the lab, and he brought on a number of brilliant minds from all over the world, many of which are still working in cancer research to this day.

He became fascinated by dose fractionation during

radiotherapy trials in the 1960s and 1970s. That is, dividing radiation doses into several smaller doses to enhance

the therapeutic effects while minimising the damage to healthy tissue. As a result his own work mathematically modelled how radiation interacted with tissue. He advanced the concept and

also defined the bioloigically effective dose and ultimately set the standard for predicting

radiation damage when the dose rate and dose-per-fraction rate were

altered. This naturally put him at the forefront of a paradigm shift in the 1980s. The current formula was proven to have a few inconsistencies and so it gradually got replaced

by his more linear-quadratic formula working more on dose per fraction,

number of fractions and also lag time for tumour response. His expertise on dose escalation led to the development

of Tomotherapy, a radiotherapy system that delivers precise doses of

radiation to tumours while allowing physicians to monitor treatment

with a built in CT scanner. I think Jack may have also worked in Brachytherapy too. That's basically a demanding but incredibly effective method of inserting radiation seeds directly into a tumour via a catheter, enabling precise localisation of the dose.

The overall impact of his work solved many problems in the management of

doseage errors, providing

rational methods for adjusting dose, and helping

to improve the consistency and safety of the entire practice of

radiotherapy.

This whiteboard seems to have once been used to record the results of experiments here, but it's now blank. Not that I'd be likely to understand anything written on it even if it was all left behind.

Now this is intriguing! This is a tape or data cartridge, and recorded on it is something called Giserver from 2008. A quick google seaerch revealed that Giserver is some sort of Linux software.

The lab also had these tiny featureless rooms with heavy doors that felt much more sterile than the other lab rooms.

These rooms felt more like cells. The only features were the sinks in the corner. Clearly these were used for some sort of experiment with the radiotherapy gizmos.

There's also this big heavy door that was several inches thicker than the average door. With all the shit hanging down from the ceiling, it was a bit of a challenge to open, but I was able to squeeze into it.

I actually almost missed it. It was very subtly placed in a narrow coridor.

The room was tiny, and once again with a teeny sink. Given the width of the doors and walls, I just knew this must have been a sterile environment used in some lab experiment.

Well... I wasn't the only person in the building, and the ones who were here, while content to let me do my own thing, were pulling the long bulbs out of the ceiling lights and smashing them over each others backs. Given that everyone had a torch because we were here at night, and these guys were making a lot of noise, I knew anyone walking by would know people were in here, and I totally considered this room as a hideout just in case the police did show up and arrest the vandals. The door was quite difficult to notice when it was shut, and it was pretty heavy. Of course I'd have nowhere to run to if I was discovered. The priority in that scenario, of course, would be to convince the police that I wasnt with them, and then make my escape. One of my own personal urbex rules is- when humans are involved, alway have a back-up plan.

To give credit where it's due, one of the guys did break off from the pack to follow me around instead, evidently looking for a bit more civilisation. Hats off to him. I forget his name.

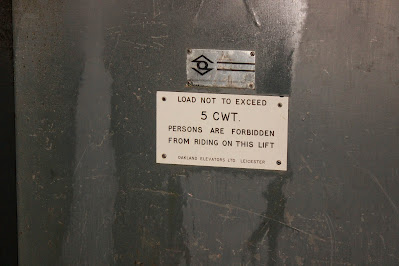

There's this really adorable little elevator at the bottom of the hallway.

No humans allowed. This is my kind of elevator. Evidently it was for transporting equipment, not people.

But alas, I had to take the stairs.

The wires to the plug sockets have been cut for some reason.

The stairs are in a beautiful state of decay.

And look! There's still curtains hanging here, with nature creeping in and peeling walls. I know people prefer pristine "time capsules" but I love natural decay.

Another elevator. This ones human friendly.

The labs on the upper floor are in a similar state of disrepair, but there's a lot of stuff left behind.

Following Jacks retirement in 1988, the lab was managed by a woman named Julie. Julie was well known in radiation research circles, famous for questioning old methods and introducing her own bright ideas. She was also great at explaining complicated concepts to students, and often the students would turn to her for explanations if they didn't understand some of the science jargon. Alas, if only she was here to help me with this blog. But quite sad and ironic, she met her end at the hands of breast cancer.

Julie was a well-liked person, nicknamed Queen Juliana for her air of confidence, and regarded as a "first timer" in that she only needed one metaphorical kick to score a goal. She obtained her PhD in 1968 with a thesis displaying the cellular variations of two types of cancer called carcinoma and sarcoma.

Her own impact on cancer research was pretty impressive. So impressive that I don't understand much of it. Something to do with furthering something called the skin clone-counting technique using deuterons from a particle accelerator called a Cyclotron, which sounds like a Transformer and was the most powerful type of particle accelerator in the world until it was out-performed by the synchotron in the 1950s.

She headed a very lengthy program to investigate late radiation reactions, because while there were plenty of tests for radiation reactions, there weren't many for late complications.

Functional

damage was measured in mice, such as their bladder output, how well their kidneys were kidnefying, how much waste was in their blood, the breathing rate in their

lungs, and the faecal output from their teeny mouse anus.

Her experiments also caused the (at the time) current formula for measuring standard radiation dose and target to skin distance to be replaced with more biologically oriented modelling. In addition to that she was able to demonstrate that the total

dose for multiple small fractions of radiation treatment needed to increase in a very different way to

the then-accepted formulas. At the time the total dose would increase with the increasing overall time anyway, but she pointed out that it needed to take into consideration a delay in the population turnover time of the epithelium tissues that cover all internal and external surfaces of the body. The rise in doseage needed to take this delay into consideration before increasing, in order to make the process safer. I think. I'm translating science that's way over my head into regular human English here. I might be talking complete gibberish, but it makes sense to me.

When it came to predicting the sort of fractioned doses needed to treat bladder cancer she developed the ARCON schedule- accelerated radiotherapy with carbogen and nicotinamide.

Clearly you'd think acronyms aren't her strong point, but she surprised me once again when she named her project "Radiobiology Applied to Therapy" which she abbreviated to "Rat," as an adorable nod to her rodent test subjects.

So the lab had an entire tray full of these glass measurement cylinders, miraculously still intact and pristine amongst the carnage that was the trashed laboratory.

The lab has this important-looking doohickey. It's possibly an incubator of some kind.

Here's an office stamp, which stamps the labs address onto paperwork.

Following Julies departure from the lab, a chap named Gerald became the chairman in 1995. He'd been there since 1962, when Hal had been recruiting a radiation chemist to work on a new technique of pulse radiolysis for investigating the unstable atoms produced when aqueous cells were exposed to radiation. Hal showed Gerald the lab and simply told him to do whatever the hell he wanted with it.

Geralds work ended up involving exploring the role that chemotherapy drugs could play in destroying hypoxic tumours, and while chemotherapy had already been around since the 1940s, Geralds research saw several drugs see their trial use in 1974. He left to become a physics professor in 1976 before returning as a chairman.

I'm loving the decay on this

Periodically throughout the labs I found these circular paper graphs with a little record player style nozzle used to record information. I'm not sure what exactly they're recording though.

Pinned to a noticeboard are instructions on what to do if there was a bomb threat. I'm not sure why someone would bomb a cancer research laboratory, but lets be honest, people will trash one so it's not at all implausible.

These bottles of eye wash are still in the cabinet

There's a pack of sanitary towels floating in a bucket of water.

Ooooh, a floppy disk.

There's a calendar for 2009 still hanging on the wall.

But one of the things that amused and amazed me the most was on a shelf in one of the offices.

This stack of paper is a pile of failed job applications , complete with the personal details of the applicants and the employers notes on why they didn't get the job. I'll censor the details accordingly, and I didn't read through the entire pile, but nevertheless what I did read was quite amusing.

Poor Ashok applied for a job as a Network Manager / Support Engineer, but the notes written on his application say "No initiative. Shy, Quiet, Cant see wood for the trees."

But my personal favourite was this Chris guy. The notes read "Intelligent? No patience to see this to end." Poor Chris REALLY flopped in tht interview.

Of course, the deeper issue here is that whoever cleared out the buiding after its closure left behind a load of confidential information. The names, addresses and telephone numbes of these people are all here to see. That's pretty bad.

This office still has loads of files in it, but I didn't look through all of them.

The journal room was pretty cool. It's trashed, but there's still loads of books still on the shelves.

All of these medical journals were likely used for reference purposes and teaching others. There's a wealth of knowledge about cancer and its treatment in this room, and somehow it's all mostly intact.

It seems a shame that all these medical books are going to waste here. I mean there's probably a million copies of each one out in the world anyway, but even so, these could be put to use.

There's some more of these glass measuring cylinders on the shelves. I'm not sure exactly what they're called or what they were for.

So in addition to the labs many successes, it pioneered the focusing techniques of irradiating cells, and sub-cellular targets, and also led a lot of research into examining and quantifying the "bystander effect," where non-irradiated cells respond to irriadiated neighbouring cells.

This laboratory actually invented a tabletop x-ray microscope which was later upgraded to one that could penetrate multiple cell layers, hitting them with a continuous bombardment of electrons and adjusting the voltage when required. To do this I think they may have actually transfered pig cells into a ureter before incubating it for seven days to monitor the growth of bystander cells.

The vandalism seems a little less severe up here. One could almost imagine this place reopening next week after a deep clean.

Nature is creeping in through tbis window too.

For some reason there are pictures of Jack Sparrow and Neo on the inside of this little office cupboaerd. It's some personal touches from whoever used to work here.

Onto the best part of any abandoned building, the toilets.

A toilet for scientists working on cures for cancer, where they need reminding of basic things like turning off taps after use.

Well, it's still in better condition than the toilets in some pubs and clubs.

At the far end of the building was this really ominous looking stairway with brick walls. I actually love this staircase just because it's so weird and bleak. And it leads aaaaaall the way down to the basemen.

At the bottom of the stairs, the basement actually started with this little store room housing a fairly retro PC.

Look, kids! Computer monitors used to be boxes!

No idea what this is.

There's an old photocopy of a CCTV camera pamphlet. It's not got a date on it but it looks pretty retro.

A quick flick through revealed that these are scans from a copy of Laboratory Equipment Digest from 1986.

There's this old laboratory whiteboard. Plus the local kids have gone a bit mad with the graffiti down here.

It seems they're exploring their sexual identity via scratching the shit out of a wall in an ababndoned laboratory. Are they trying to say that Covid makes you gay?

Alas, the rest of the basement was shut away behind a big glass door. I turned back to find an alternate route, but once I had done that, I heard a collossal smash. One of the folks trashing the place had come across the glass door and just obliterated it. I wasn't really happy but they were leaving me to it, so I just decided to see what I could see before they destroyed that too.

The basement is just more laboratory, but somehow has a much darker vibe. It's creepier down here. Obviously, basements are always creepier than being above ground, but when it's dark outside it really shouldn't make that much of a difference.

There's some pretty cool machinery down here. Check this out!

Why does a cancer research laboratory have stuff like this?

It gets better though! There's a freakin' fork lift!

There's still a key in it, too. It's probably still operational.

This makes mention of a "Van de Graff area," and that is intriguing. It obviously refers to the American physicist, Robert Van de Graaff, who invented the Van de Graaf machine, which is an electrostatic generator, or essentially a particle accelerator able to produce vast quantities of energy. Plenty of small ones are available for hobbyists, and often used by schools to fascinate children by making their hair stand on end using electricity. But I imagine a laboratory has a much larger one. Probably not the largest- that's in America and I've seen videos of it shooting amazing bolts of lightning and also using electricity to make musical energy bursts or something.

I wonder if the Vann de Graaf generator is still here. I mean, whoever cleared out the lab couldn't be arsed to shred some job applications, so what are the chances that they wanted to lift a massive particle accelerator?

It's probably quite valuable so I guess it's hit or miss.

The toilets here are unisex. I guess scientists looking at beating cancer have bigger concerns than the reproductive organs of the person in the next cubicle.

The best part is, when I look at this picture I can still smell it.

So from what I've read, by the 21st Century the lab was starting to show signs of needing a little TLC. The lab was funded mostly by cancer research campaigns, making about three million a year in 1998, but I have no idea how far that stretches in areas of work where cells are irradiated on the daily. I inagine that's expensive business.

But regardless, the building was becoming derelict, and people even started resigning because it wasn't safe. The decision to close the lab was planned in 2003 but was apparently met with some protest, and that's understandable. I think something like cancer research deserves as much funding as it needs.

The decision was finalised to relocate the lab in 2004, and it finally closed in 2008, reopening its facilities elsewhere. So it's not so bad. The work has continued. We haven't really lost anything.

Obviously it would be good if the building could still be used for something, but an assessment in 2019 concluded that it was not fit for purpose.

Here we go. This sign makes mention of the Van de Graaf basement. We're getting warmer.

In the end, unable to locate the door, I decided to take the fun route, crawling through that square hole in the wall there. It brought me out in this tiny room with a wooden staircase leading upwards.

There's loads of machinery still down here.

"Do not evacuate the VdG tank unless you are sure that the acceleration tubes are under vacuum. Otherwise you can do serious damage to the tubes. They are okay under inward pressure but are not designed to withstand outward forces."

So this is one of those signs that is in English but makes no sense to my feeble brain. One thing does stand out though! VdG! Van de Graaf!

I turned a corner and there is was. An abandoned particle accelerator! Now that's a first for me.

Alas, my pictures don't do it justice. It was huge.

From whht I understand, which is very little, the columns had whirling fabric belts that generated electricity.

There's this big overhead crane.

And this hanging control panel. Seems fairly simplistic.

Oh, who am I kidding? I have no idea how this doohickey works. Only that it was once capable of generating huge quantitiesof energy. What I do know how to do is climb it so that I can get a look at the top.

I think the big silver domey thing actually fits over the top, but has been taken off for some reason.

This particular Van De Graaf accelerator is apparently unique, but I can't say I know enough about them to know why. It's a lot larger than some but not nearly the largest in the world. There's a huge one in Pennsylvania nicknamed the Atom Smasher. I have heard that the larger the domed top, and the higher it is from the ground, the greater it's potential. I guess size does matter, folks.

There was this huge tank with a ladder next to it, so I decided to climb up there to take in the view..

I guess with more lighting and an actual tripod, and actual photography skill, someone could actually do the van de graaf machine justice, but fuck it. I haven't actually seen any other shots of this from other explorers. That doesn't mean there aren't any. I'm not arrogant enough to claim to be the only one. But with the access to this building being as sketchy as it is, it's dodged the herd a bit. The herd like walk-ins because they're easier to loot.

One final spot remained, and that was the roof!

There's some graffiti up here. Some kind of boy band don't like squirrels. And then there's the view...

It was peaceful up here, away from the carnage downstairs. I was miffed that people had been smashing the place, but rooftopping always calms me down. Urbex is great for my mental health anyway. It quite literally saved my life. I guess that's why I'm so protective of it. As someone who generally struggles to relate with the human population, it's important to have something to take the edge off life, and when those same humans then come into my little world and shit everywhere, it's quite demoralising.

With cancer research it's doubly annoying. Cancer is serious business. And if you know anyone who has survived cancer, then there's a strong possibility that the treatment they recieved was developed, and tested in this building by the brilliant minds whose former offices now sit trashed, and were still being trashed even as I sought to document them. Those who trashed it should be ashamed of themselves, because one day it could be them or their loved ones who need the treatment that was developed and perfected here.

With rooftopping, the enerrgy involved, and the view, and the cold air, it just sooths all the stress away, and all that matters is the present moment. That's why I love it.

Over in the distance are the lights of some town full of thoiusands of stressed out humans, and then there's me, enjoying the fuck out of life on a roof.

And that's all I've got.

To conclude, only climbers could access the lab on my particular visit, which makes it not for the usual herd-based pin-swapping types. But if you like a challenge, then it might be of interest. If you like stuff pristone, then it's not for you. Unfortunately with the local kids well aware of it, this is probably the best I'll ever see it, so I have no plans to return. It was something different though. I really enjoyed it.

My next couple of blogs are on my Shropshire blog, because they're local. One is a pub and the other is a mortuary. I'm looking forward to both. In the meantime, follw me on Instagram, and it's lesser populated but better algorithmed cousin, Vero. I'm also on reddit, Twitter and unfortunately Facebook.

Thanks for reading!